Written by Bill Orzell

[From the 2025 Summer Magazine]

Fasig-Tipton Sales Pavillion

Photo Courtesy of the Beatrice Sweeney Postcard Collection

Thoroughbred yearling sales have taken place at the Spa since the early years of the twentieth century.

The first weeks in August bring an additional excitement to Saratoga Springs, which adds measurably to the Race Track exhilaration, when the annual yearling sales occur at the Fasig-Tipton Pavilion.

Thoroughbred yearling sales have taken place at the Spa since the early years of the twentieth century, yet in 2024 the sales gross exceeded $100,000,000 for the first time.

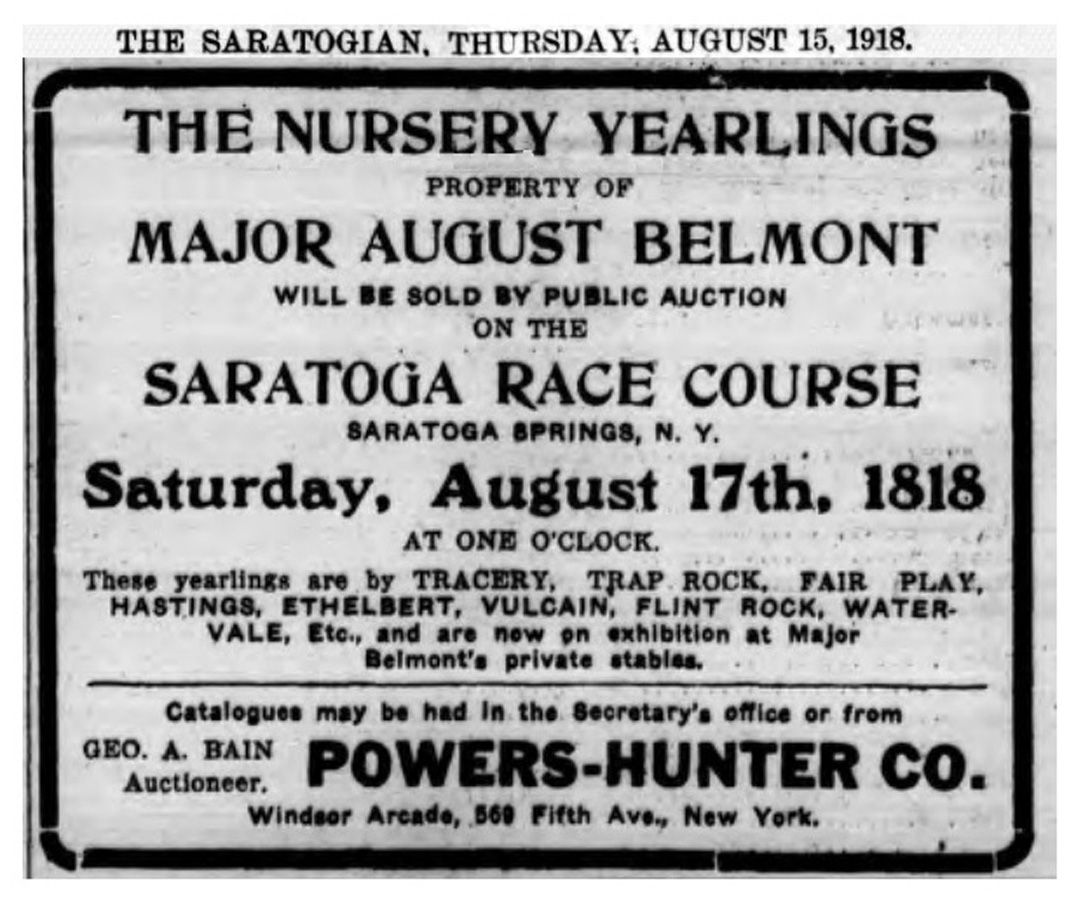

Powers-Hunter Company auction notice of Major August Belmont’s yearlings to be sold at the Saratoga Race Course paddock, which would include Man o’ War. The Saratogian committed a rare typographical error in the date of the event.

The Fasig-Tipton Company entered as a participant in 1917, with their purchase of property on East Avenue and George Street, giving them the advantage over existing auction companies like Powers-Hunter and the Kentucky Sales Company, who conducted their auctions in the race track paddock prior to the day’s races. Interestingly, all the competing companies would often hire the same auctioneer, the venerable George A. Bain, to deliver the chant.

The big advantage Fasig-Tipton had in building what they termed their “sale mart” was the ability to stage auctions following the race day and even after dark. During the inaugural season of 1917, the Fasig-Tipton auction would begin at 5:30 p.m., which was found to interfere with the much anticipated cocktail hour. Always sensitive to the preferences of the marketplace, Fasig-Tipton shifted the vendue start time to 8:30 p.m.

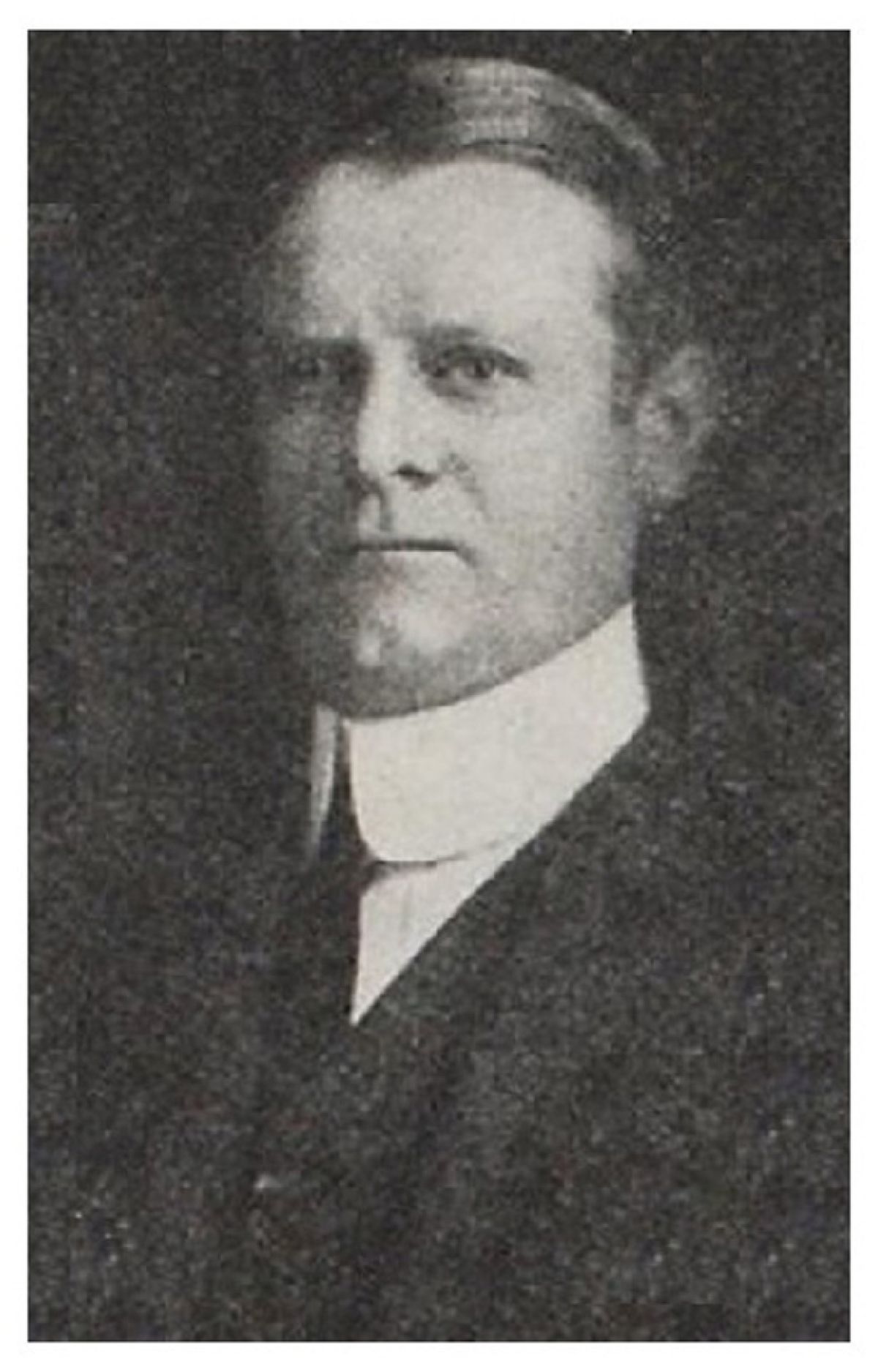

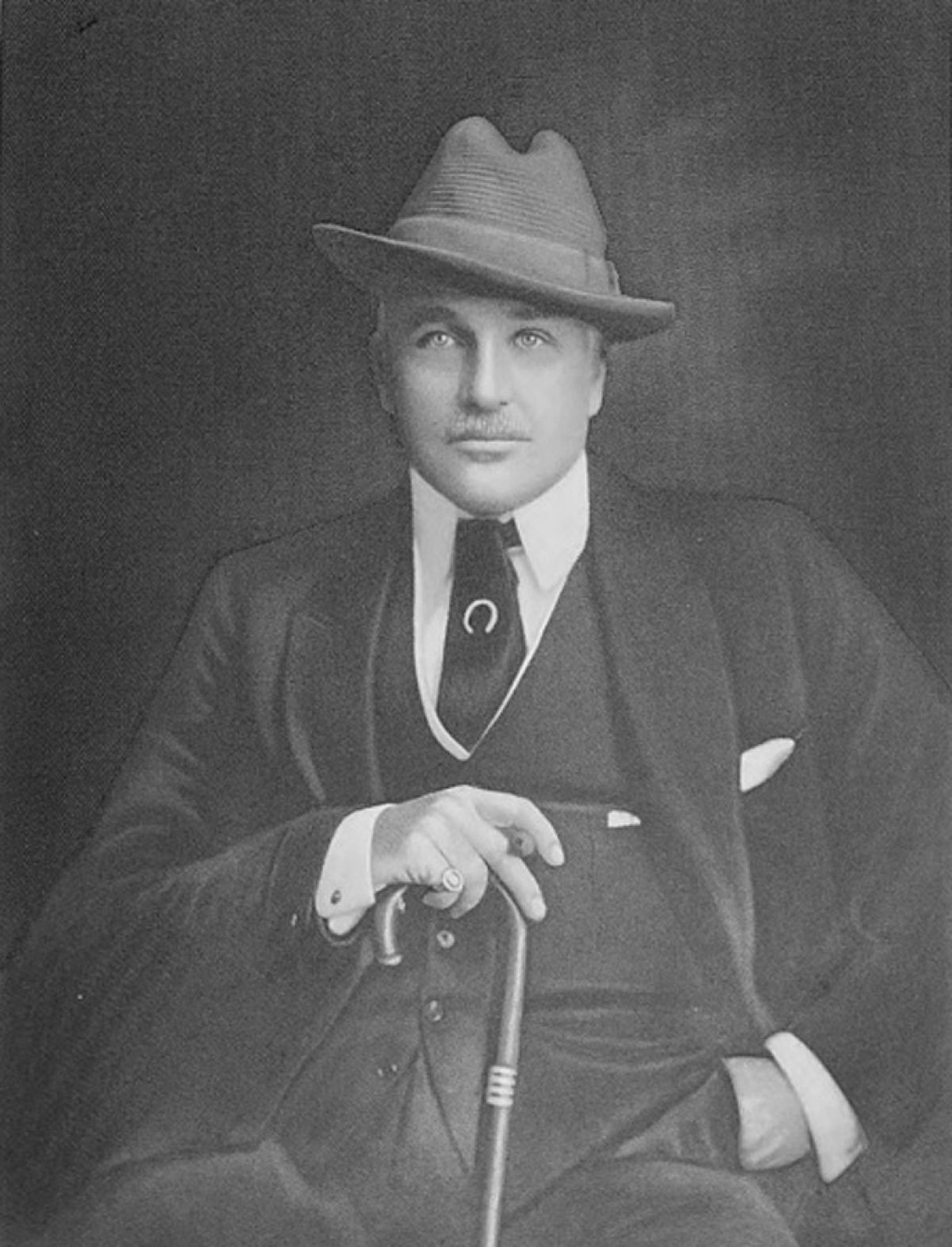

Former Congressman and candy mogul, George W. Loft. Image from New York City’s Silver Jubilee 1923.

This allowed patrons who had attended the day’s racing to begin the evening’s social interaction at the sales pavilion, fostering a formal dress cocktail party atmosphere and an event in itself, under the warm glow of electric lights.

The auction format was much different from what we are used to today, because during the reign of Edward J. Trantor at Fasig-Tipton, the sales were conducted every weeknight following racing during the entire meet. Also, entire consignments would go to the ring in a block, without integration with fellow consigners.

The large breeders would often have their own night in the auction pavilion, with the ever-capable Fasig-Tipton staff all sporting white dinner jacket tuxedos, enhancing the prestige of the evening. The original auction pavilion resembled a barn in many respects, yet it was a forum of competitive dealings where “money talked,” and the product was the pinnacle of Thoroughbred breeding.

These major revisions in the annual yearling auctions in 1917 would set the stage for the following years and decades, with some of the most notable happenings during the auction season that occurred in 1918.

The world, for the first time, was at war in 1918. The impacts of the global conflict were felt everywhere and all commodities shifted to a premium. The First World War also fostered the first worldwide pandemic, as what was termed the “Spanish Flu” decimated populations around the globe, spread by the fighting forces and refugees.

The present day elliptical pari-mutuel building and racing offices at Saratoga Race Course had been built as a paddock as part of the 1902 improvement of the grounds. Powers-Hunter staged a sale there on August 3, 1918 where the yearlings of Hall of Fame breeder John E. Madden were consigned. Mr. Madden donated a yearling filly, whose sale proceeds would befit a unique charity which collected baseball equipment and tobacco for American soldiers, or “Doughboys.” However, the afternoon auction format seemed to suppress sales and only moderate prices were realized.

The trench warfare stalemate in Europe spurred aviation development as never before, and long range zeppelins and swift pursuit planes roared into the blue yonder. The second week in August brought word from France about the Battle of Amiens and the beginning of a string of Allied offensive successes. Newspaper editors needed to differentiate between the US President and President of the Saratoga Association, who shared the surname Wilson. Enrico Caruso, tenor of the Metropolitan Opera Company, was in Saratoga to give a concert at Convention Hall; at the track Clubhouse he attracted much attention in the box of Chauncey Olcott. Concern was rife that Boston’s star pitcher, Babe Ruth, had been notified by his draft board to find “essential work” by September 1, which could prevent his post-season with the Red Sox. Much surprise and regret was expressed over the murder of saddle and harness maker Alfred Mann of Queens, in the barn of candy mogul George Loft. The victim also performed night-watchman duties for that stable, and he was robbed of what his hard work had yielded.

During the First World War, a number of special auctions were added in order to raise funds for local charities.

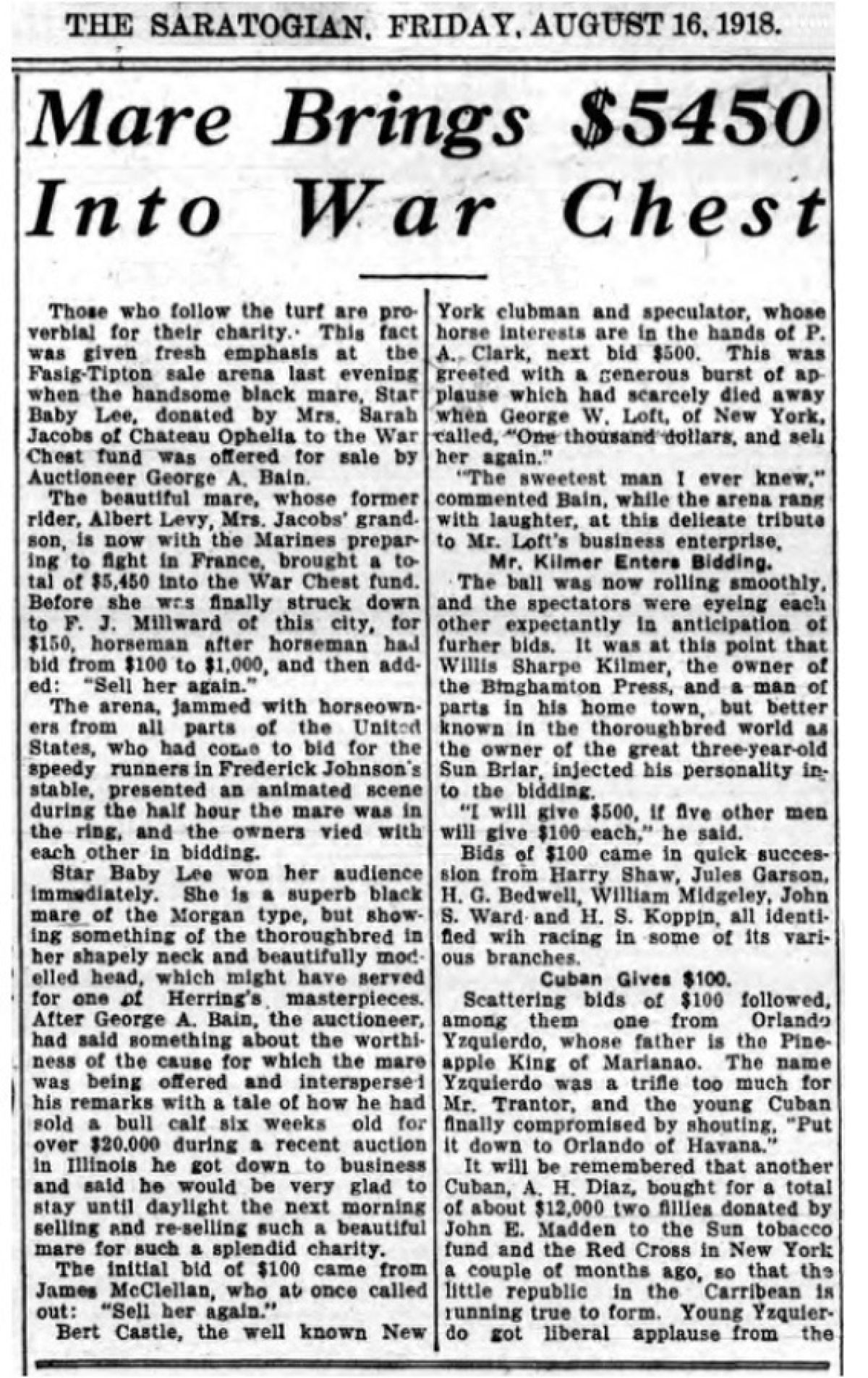

Willis Sharpe Kilmer, thoroughbred owner and breeder from Binghamton, goaded others for additional bids on the War Chest Horse. Image from Binghamton and Broome County, New York 1924.

Attention shifted to the Fasig-Tipton sale on August 15, when the stock of Frederick Johnson, operator of Scarlet Gate Farm near Lexington, would go to the block. Mrs. Johnson was known to the art world as Mary MacKinnon, and the couple had a summer home and studio on Myrtle Street at the Spa.

Another horse to be auctioned that Thursday evening would benefit the Saratoga War Chest, an amalgam of local charities. The War Chest Horse was not a Thoroughbred, but a handsome black saddle and harness mare, known as Star Baby Lee, donated by Mrs. Sarah Jacobs of Chateau Ophelia on Lincoln Avenue, which boasted its own path to the race track. Star Baby Lee, a docile palfrey horse had belonged to Albert Levy, Mrs. Jacobs' grandson, now with the Marines preparing to fight with fellow “Devil Dogs” in France.

The previously mentioned auctioneer George A. Bain, whose appropriate initials were GAB, was determined to build up the War Chest by obtaining more than the calm mare’s actual value, and felt her offering would attract persons beyond the realm of their typical bidders. This sale would attract those with a curiosity about Thoroughbred racing, but not necessarily a financial interest, to the sales pavilion. It is a delightful tenet, frequently practiced by Fasig-Tipton for decades since, into our time.

The jammed arena welcomed the War Chest Horse with great anticipation. Star Baby Lee was initially knocked down for $100, and the new owner extolled auctioneer Bain to “sell her again.” This was greeted with a burst of applause, normally frowned upon at an auction ring, and a new bid of $500. This was immediately topped by George W. Loft of candy store fame, who called out, “$1,000, and sell her again!” Laughter nearly brought down the house when George Bain replied, “the sweetest man I ever knew.”

Binghamton owner/breeder Willis Sharpe Kilmer, known to use up most of the oxygen in any room, issued a challenge, and offered $500 if five others would come across for $100, which was quickly met. Seventeen $100 bids came in, and three bids greater than $300. Mr. Kilmer made his matching offer a second time, and also offered $100 apiece on behalf of the United States Hotel, Casino Restaurant and his trainer Henry McDaniel, with the credit assurance that “if they don’t pay it, I will.” The mare was eventually knocked down after $5,450 was collected for the War Chest, the equivalent of 8 brand new Ford Model T automobiles. Fasig-Tipton made a donation of their time and expenses to the War Chest.

Acclaim for the War Chest sale was quickly replaced by anticipation of the next auction the following Saturday, to be staged by Powers-Hunter in the race track paddock prior to the running of the day’s race card, which would include the renowned Travers Stakes. August Belmont, chairman of the Jockey Club, sold very few yearlings, yet 1918 was an anomaly due to his voluntary involvement in the conflict. Major Belmont served in Europe as a procurement specialist for the American Expeditionary Forces, and needed to step back from racing. He decided to sell his entire foal crop of 1917 as yearlings, due to his Nation’s call to duty.

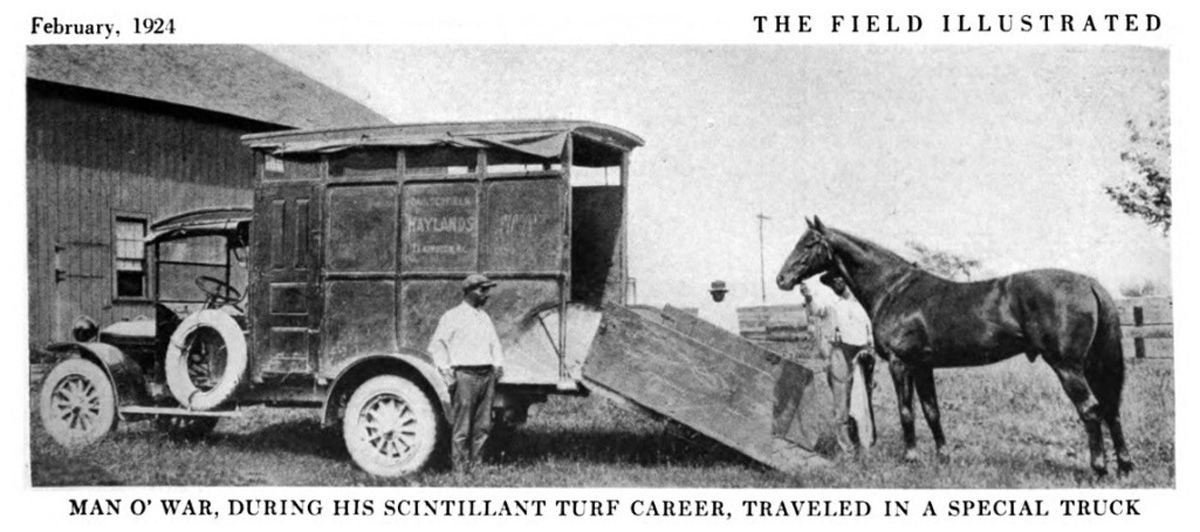

Nearly all horses arrived at Saratoga and other race courses by rail, and were walked from the train station to the track. Due to Man o’ War’s value, he pioneered a new form of transit.

The ten yearling fillies, produced at his Nursery Stud near Lexington, had their coats clipped and were made pretty for the sale by the staff in Kentucky, and shipped by rail to Saratoga and consignment to the Powers-Hunter Company.

August Belmont thought he had a deal to sell his fifteen yearling colts to Howard Oots, but at the last minute this arrangement fell through. These colts, which included Man o’ War, had not been prepped for the sales ring, yet needed to be dispatched quickly to make the Saratoga Sale.

Many conjecture it was the unkempt appearance of Man o’ War that suppressed his sales ring appeal, and allowed Sam Riddle to bring the hammer down for a mere $5,000.

We know from the similar price realized by Star Baby Lee a few nights before, that this amount was about the equal of eight new Tin Lizzies, not peanuts for sure, but possibly not what could have been expected. The Thoroughbred Record noted after the sale,

“The first high price paid was $5,000 which S. D. Riddle paid for Man o' War, a good-sized and well-balanced chestnut colt by Fair Play-Mahubah, by Rock Sand. This colt is bred very much like the wonderful horse Friar Rock, for which John E. Madden paid Major Belmont $50,000.”

Man o’ War

With two entries in the Travers Stakes field of four later that afternoon, Willis Sharpe Kilmer did not purchase any of the Belmont Stock. His swift imported colt Sun Briar won the Travers Stake over stablemate and Kentucky Derby winner Exterminator, Preakness winner War Cloud, and runner-up Johren, who had won the Belmont Stakes.

Before that August ended, Sam Riddle would purchase a Saratoga residence on Union Avenue. An Armistice was signed in November, bringing to a conclusion the “War to end all Wars.” After a two year search and investigation, John Lovell Hays admitted guilt in the murder of the night watchman in the Loft Barn, and went to the “Big House” at Dannemora. The Fasig-Tipton business model succeeded, and in early 1920 they bought out rival Powers-Hunter. The Company’s sales remain a fixture of the Saratoga track season.