[From the 2025 Spring Magazine]

I love seeing our town's entrance sign proudly proclaiming our city slogan, "Health, History, Horses."

Consequently, for Women's History Month, I wanted to honor three women who uniquely contributed to our health and well-being. My list of potential honoraries was long, so I narrowed it down to women who are no longer with us but were alive during my lifetime, giving me a firsthand perspective of their impact.

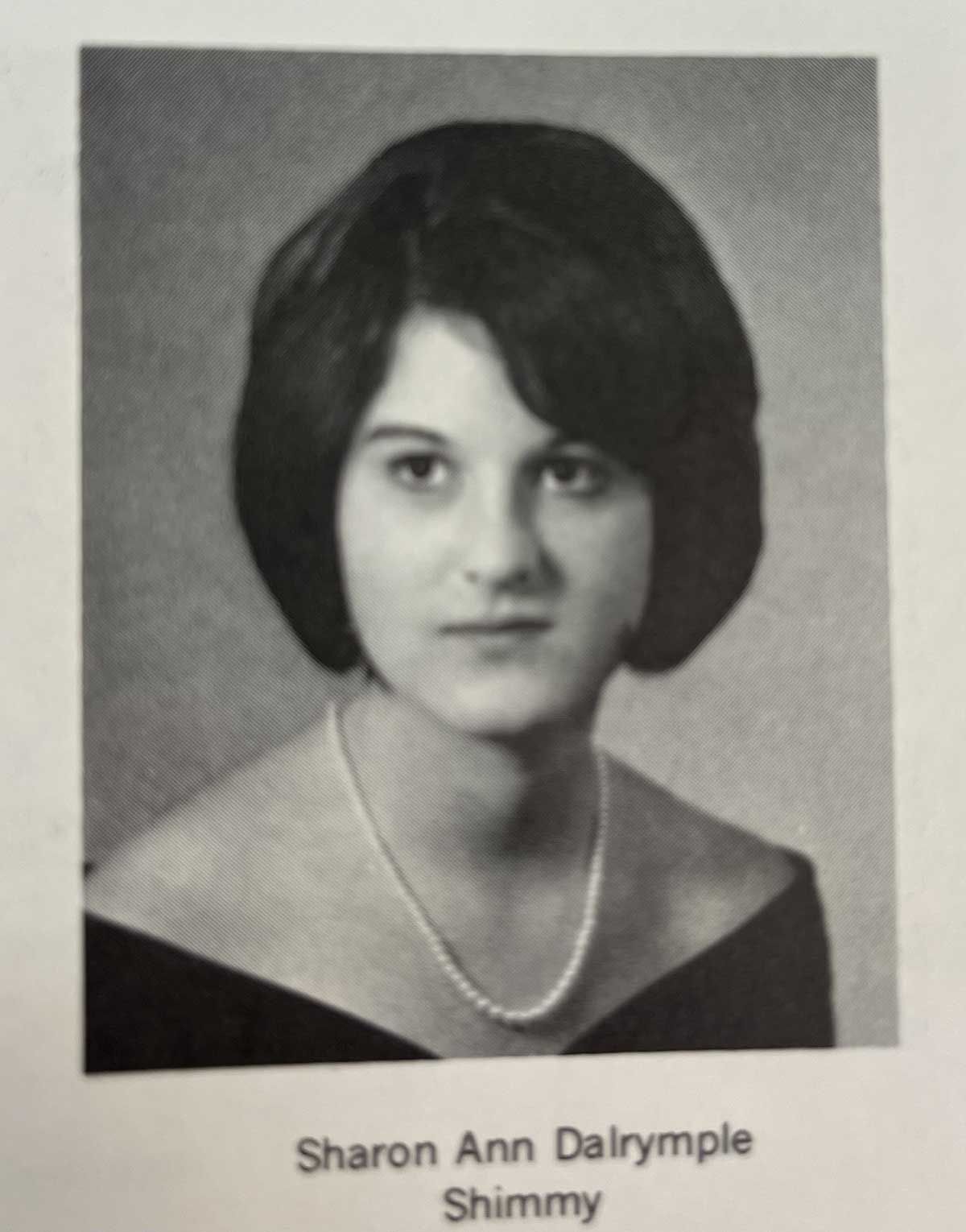

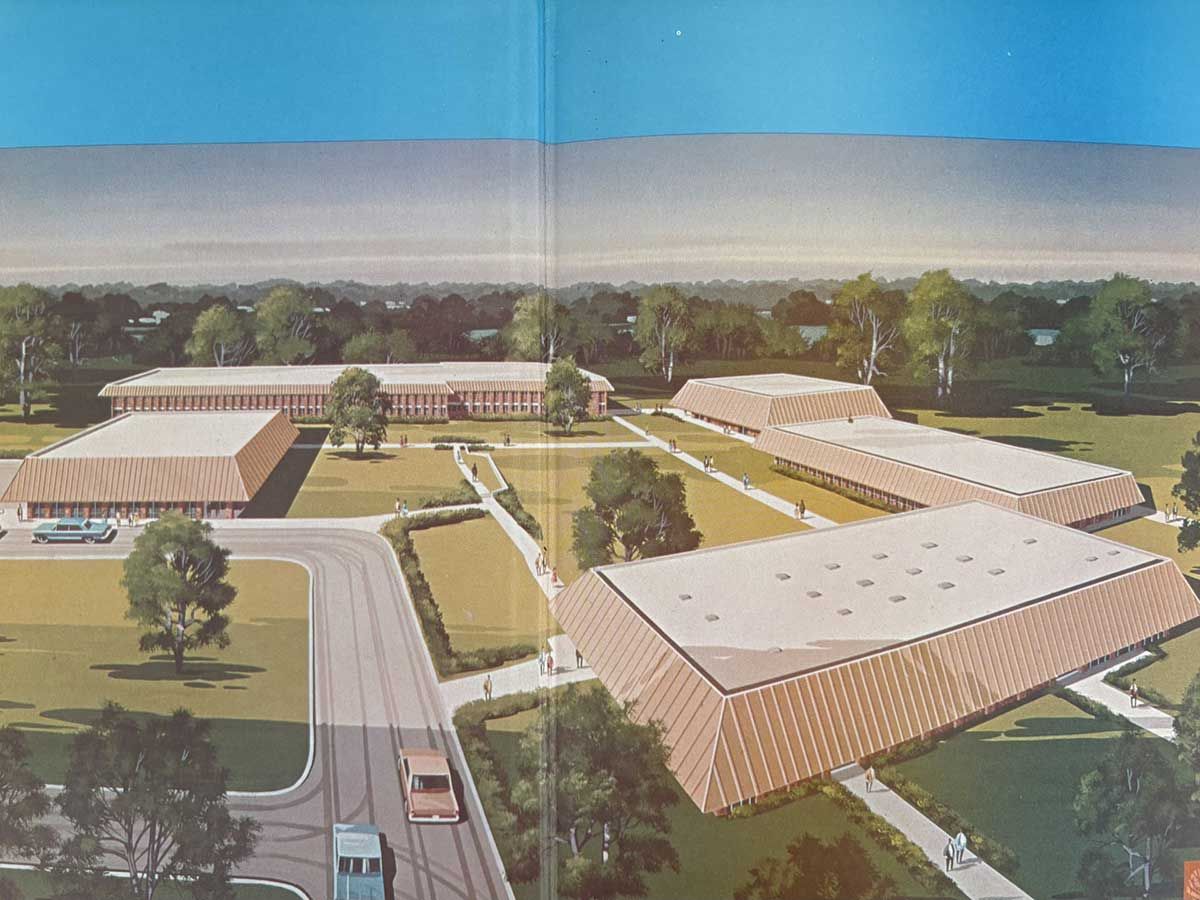

On the cold morning of February 1, 1966, with the temperature at 6°, high school senior Sharon Dalrymple woke up and reached into her closet at 70 Outlook Ave. It was her first day back to school after recovering from strep throat. As she thought about her mile long walk to the newly opened high school campus on West Avenue, she boldly selected a pair of navy-blue wool slacks from her closet. The Texas-designed campus had five separate, unconnected buildings, meaning students often had to endure chilly outdoor walks between them.

Before long, Principal Onody spotted her in the hallway and sent her home for violating the unwritten policy of no pants for girls. On February 4, my mother, Barabra Stone, while working for the Post Star, reported, "Mr. Onody said he believes in a 'wholesome and showcase look' at the school." School attorney Ted Grey described her actions as "an open rebellion against school authority."

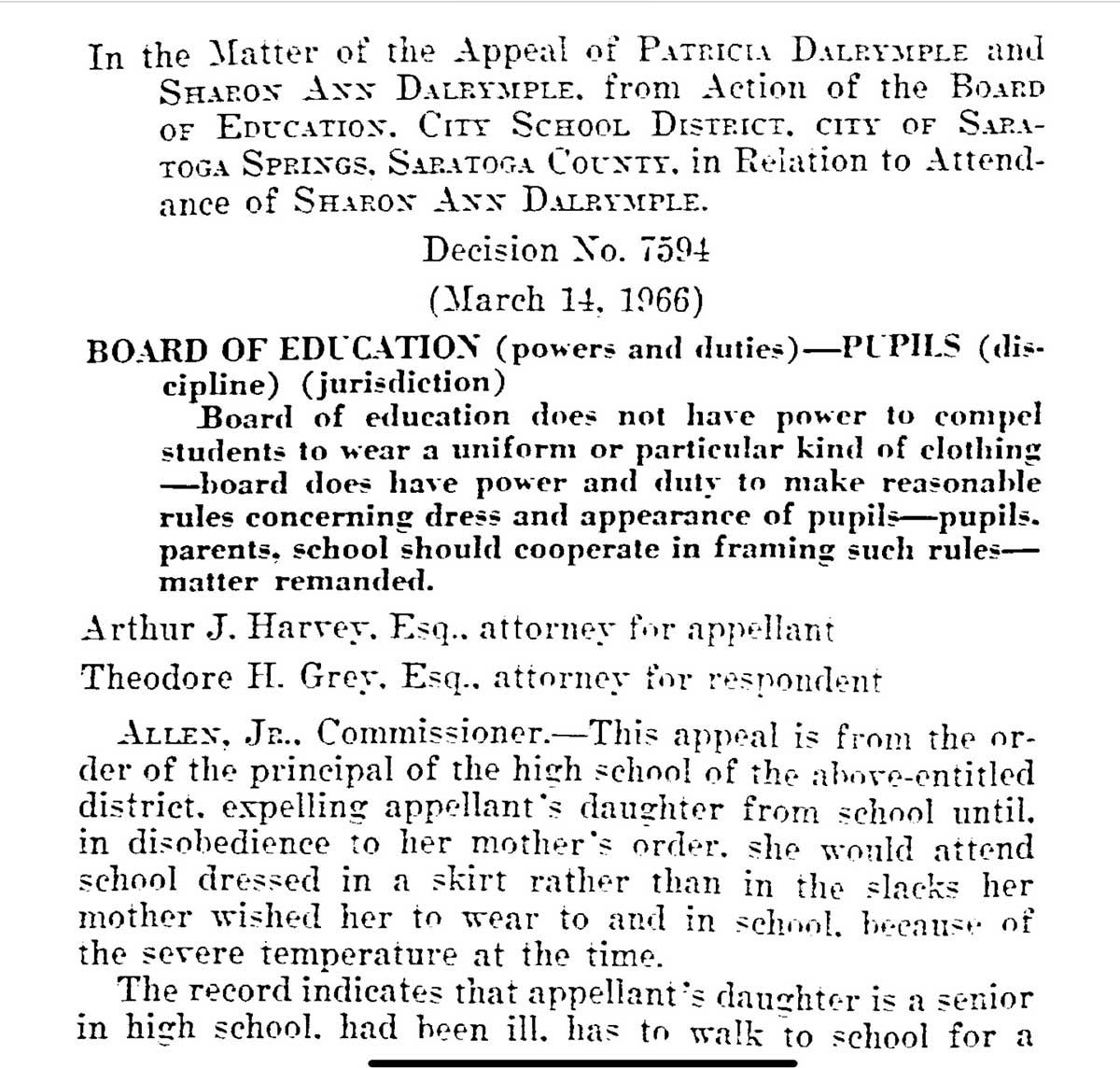

A six-week-long heated legal debate ensued. Sharon and her parents appealed to New York State Education Commissioner James Allen for an injunction to allow her to return to school and wear pants. It was granted.

For at least a month, this case became a topic of dinner conversation in our house. My older sister was Sharon's classmate at the newly constructed campus, and my mother wrote seven articles for the Post Star detailing various aspects of this landmark case. Each evening, our family discussed several questions: Was it wise to have a Texas architect design a school for our upstate New York climate? Did our all-male Board of Education understand that most girls wore knee socks with their skirts, exposing bare skin to the cold? Should a school expel a student for not following their dress code? And are girls' pants just for "recreational purposes?"

Newspapers as far away as Anchorage, Alaska, featured articles about the landmark "Dalrymple vs. the Board of Education" case.

Mr. and Mrs. Dalrymple believed it was their right as parents to dictate what Sharon wore to school. The Board of Education believed their authority was in question.

On March 15, 1966, Commissioner Allen decided that school authorities had no right to threaten expulsion if a pupil wore slacks. However, he also stated that local authorities can make reasonable rules regarding the dress code.

I applaud the late Sharon Dalrymple Weigle for her bravery. She paved the way for future girls like me to wear pants to school on cold winter mornings in upstate New York.

Beatrice Sweeney prioritized her family above all else. Living across the street from her 203 Union Avenue home in the early 1960s, I witnessed firsthand her maternal devotion. Whether it was her careful attention to her children's needs or the grace with which she balanced family and civic responsibilities, Bea exuded warmth and quiet strength.

Aesthetically pleasing surroundings were important to her. When her family moved to 34 Lefferts Street in 1962, she furnished their new home with a discerning eye, creating an antique-filled living room in soft creams and powder blue—so refined it could have graced the pages of Better Homes and Gardens. But her attention to beauty didn't stop at home. She extended her talents outward, ensuring that her family lived in a city that honored its architectural heritage.

In 1968, her life was a whirlwind of responsibilities. As the wife of a New York State Supreme Court Judge, the mother of Kevin—a high school senior bound for Williams College—and Maureen, a bright seventh-grader, Bea had little free time. The following year, she took on another significant role: city historian. "She had Super Woman powers," recalls her daughter Reney. "It was as if she had a magical way of finding more than 24 hours in a day."

Despite her packed schedule, Bea was deeply committed to causes she believed in—especially the Canfield Casino and Congress Park, which she saw as the heart of Saratoga Springs. When a developer secured approval to lease four acres of Congress Park for a 150-room hotel addition to the historic Casino, she was outraged.

In 1968, from a small office she had carved out in the basement of her Lefferts Street home, she secretly typed a letter to New York Times architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable. Bea's plea was urgent: help stop a proposed 150-room hotel addition to the historic Canfield Casino and the loss of 4 acres of Congress Park.

Bea's plan worked. Huxtable's March 10, 1968 column "Saratoga's Losing Race” said, "Saratoga's news is a little more interesting than most because it is a little more outrageous. The city will hold a public auction on March 19 to lease over four acres of Congress Park for a 150-room hotel. Turning a park into real estate is a barbaric betrayal of public trust anywhere, but in Saratoga, it has particularly interesting cultural connotations."

Sweeney continued to work strategically, using her voice in ways that carried weight. After becoming City Historian in 1969, she wanted to ensure the protection of our historic buildings. She completed applications for the Casino, the Drink Hall, and other local landmarks to be on the National Register of Historic Places.

Her list of accomplishments is exhaustive: professionalizing the Saratoga Springs Historical Society, advocating for the establishment of the Preservation Foundation, and serving on the board of Yaddo, Skidmore, and the Katrina Trask Garden Club are just a few examples of how she improved the health and well-being of our community.

Sweeney's plan was brilliant. Huxtable's piece brought outrage and national attention to the hotel addition. Soon after, the developers withdrew their proposal.

Like Beatrice Sweeney, Jane Wait was a woman of boundless energy. As the wife of Adirondack Trust Company president Newman E. Wait Jr., she had numerous social obligations. As the mother of four children, she balanced the demands of family life. Yet she still found time to enhance Saratoga's well-being through education, the arts, and gardening.

Mrs. Wait was my seventh-grade science teacher, and although science was never my favorite subject, I eagerly anticipated her class on life sciences. She made the subject come alive, inspiring me to memorize the name of every bone in the human body. Her enthusiasm was contagious, and each 40-minute class seemed to fly by.

Beyond the classroom, Jane Wait's impact on the community was far-reaching, especially when she founded the Yaddo Garden Association in 1991 to revitalize the deteriorating 10-acre garden, the only part of Yaddo open to the public. She volunteered thousands of hours, ensuring the garden once again became a place of peace and solitude. In recognition of her tireless efforts, a special rose was commissioned in her honor in 2012.

Her passing in May 2022 was a profound loss. The New York State Assembly honored her legacy with a three-page resolution, acknowledging her lifelong dedication to civic endeavors that enhanced the quality of life in Saratoga Springs and beyond.

Each of these women, in her own way, enhanced our community's health and well-being, proving that individuals have the power to shape history.

A note of thanks to Michelle Isopo at the

Saratoga Room in the library for her research help.